Lessons from my immigrant mother

Read a personal retelling of a mother's migration story from a daughter's perspective.

“Nearly everyone is an immigrant if you go back far enough”, I explain to my 11-year-old half-sister. “I’m not an immigrant”, she replies with a hint of pride. We share a white father, and unlike her thoroughly English mother who travelled just a few cities south to get to London, my own mother travelled several oceans. “But your Granny came here from Ireland in the 1960s, she’s white, but she’s an immigrant”, I reveal. “Oh”, she says, and I can’t tell if she’s disappointed.

“We really need to stop being afraid to talk about the ‘I’-word, overpopulation is a huge problem”, my friend’s dad announces us at dinner. We are sat with his immigrant wife, my immigrant mother, and my other friend’s immigrant mother. Everyone nods.

‘Immigrant’ is a dirty word today. But to me, it describes the journey of how I came to be. The journey that started on 8th December 1971 when my then 12-year-old mother landed in Heathrow Airport from Hong Kong. How she felt travel sick, and threw up everywhere after eating yoghurt for the first time. How she found England so cold, that she once sat so close to the gas fire in their East London council flat and burned a hole in her synthetic pink jumper. How my mother was so excited to see high-rise buildings like in the American films, and thought to herself “I’ve come to a backwards country” when all she saw was low-rise terraced houses. It is the story of how my mother attempted to make spaghetti bolognaise with soy sauce.

When card-carrying UKIP supporters will immigrants to return to their ‘own country’, they want to send my mother back to her childhood home – a wooden hut in Sheung Shui with a corrugated iron roof, one bed for the five children, one for the parents, and one for the grandmother. It flooded every year and the only possession they had to save from the water rushing in was a bag of rice. It was a modest and functional house full of love, but it did not offer free education, free healthcare or a precious state-granted one day off per week for my chef grandfather.

When I get asked “where are you from from?”, or get called ‘exotic’ or ‘foreigner’, or hear “ni hao” shouted at me by strangers on the street, I imagine these people picture me taking my first breaths in this same wooden hut. The reality is a ward in The Whittington Hospital in Archway. These comments don’t hold the same threat to me as they do to my mother; despite my appearance, Britain is my birthright.

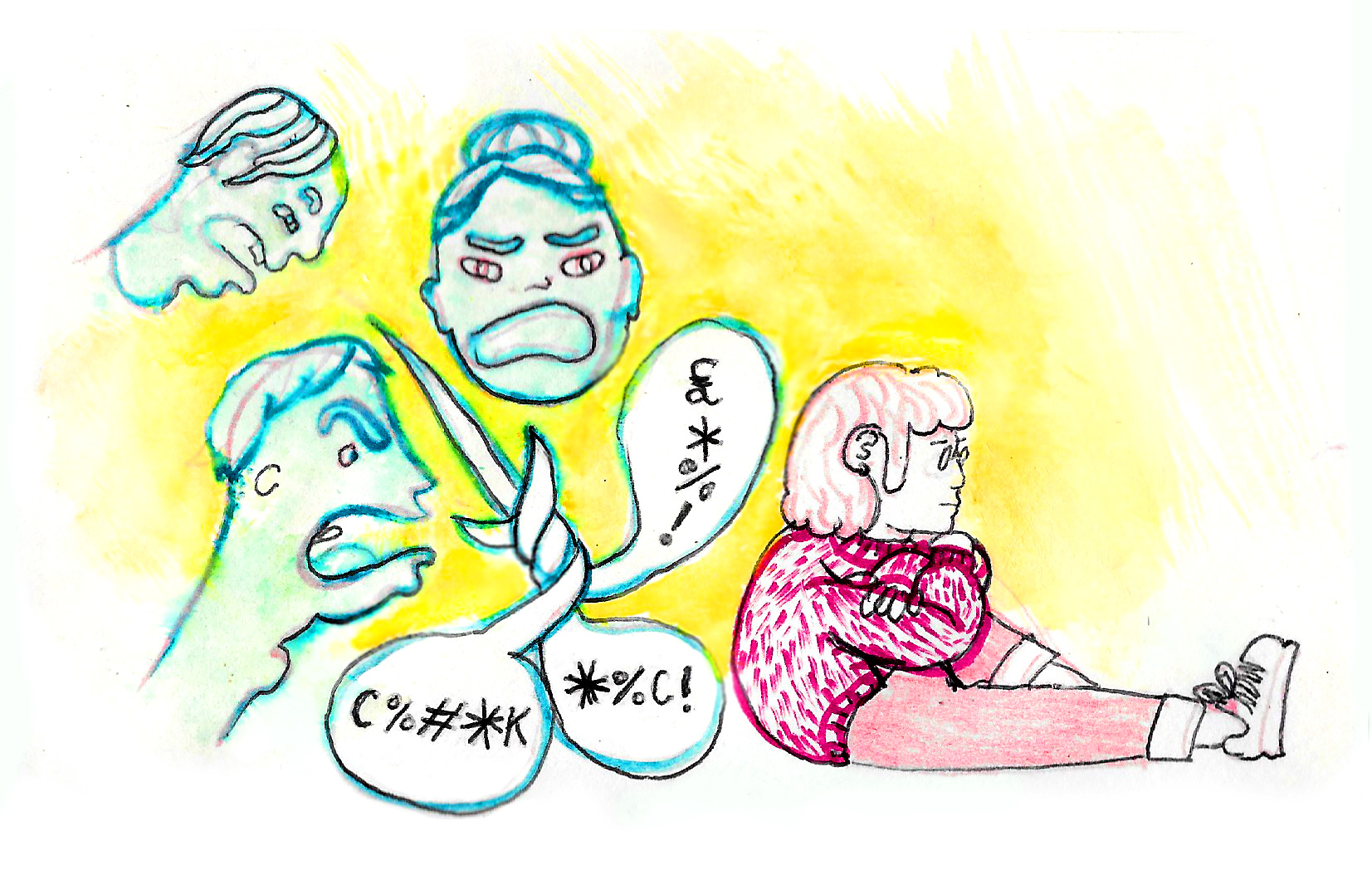

But being shouted ‘ni hao’ at is preferable to slurs like ‘chink’. “One of our neighbours used to shout this at us on the street”, my mother tells me. I imagine a white bloke™ EDL-marching-Phil-Mitchell-from-Eastenders type, but the culprit was a BBC (British Born Chinese) kid whose family owned the local Chinese takeaway. His first cousin later married my uncle.

Self-hating racism was not my mother’s biggest fear about moving to the UK however. “We heard rumours about England from our neighbours in Hong Kong”, she recalls. “Some people were so nasty. They would say things like ‘your father has already married a 鬼婆 (gwaipo), when you go over there you will meet her’. So I was quite afraid to move because I nearly believed them. They also said that England was so cold that if I touched my nose it would fall off. But we already knew it was cold because my dad would send us photos of him dressed in a hat and trench coat standing in Trafalgar Square, holding his arms out with pigeons perched on him. We didn’t even know that there was summer in England.”

Having been born and brought up by my mother in London, I’ve never known another home for her in my lifetime. I consider her a local. She knows the tube map like an old friend, always second guessing the route on Google Maps and thinking she knows better. She has learned English to complete fluency, surpassing the language level of her illiterate native classmates, and went on to complete a degree in English Literature. Yet, I’ve heard people imitate her with a ‘Chinese’ accent. There’s nothing wrong with having an accent, but she doesn’t have one. I always found it incredibly strange that she couldn’t escape a stereotype that her appearance lent her, despite her sounding like a BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) newsreader to me.

My mother’s journey was thankfully not a dangerous one unlike many other immigrants and refugees to the UK. But still I feel that maybe if those people knew her story, they wouldn’t have been so quick to pull their eyes into slits and exclaim “ching chong wa”. Immigrant stories need to be told, especially at this sinister time where people of the Windrush Generation are having their citizenships violently revoked. Let’s continue to spread these stories further than a pointless Buzzfeed quiz or a viral dog meme.

Hannah Gooding is one of the founding members of gal-dem magazine, and was Fashion Editor for a few years, but can now be found avoiding London Fashion Week to hang out with her Granny instead. Writing from experience, she mainly covers topics surrounding the fashion industry or being Eurasian, but if called upon could also write expertly about being a hoarder or how to overcome the heartbreak of not being able to afford Hamilton tickets. Hannah is on Instagram at @hannahsangooding.