Against 'Hate Crime'

on resisting the framing of racist attacks as 'hate crimes' and refusing complicity with the police

*You can listen to an audio version of this post (link: https://soundcloud.com/daikon-zine/against-hate-crime text: here).

*

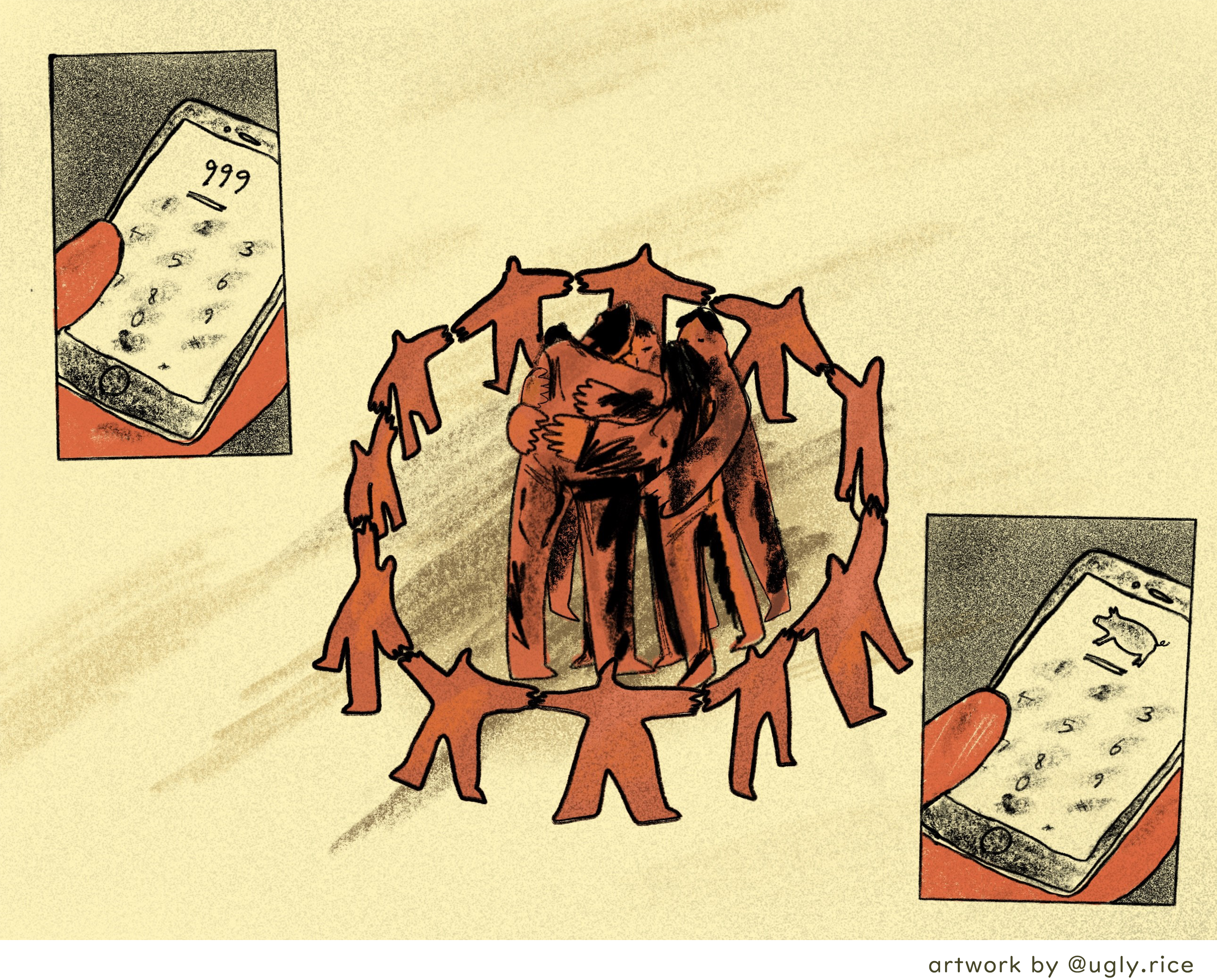

There has been a sharp increase in racist attacks on East and Southeast Asian people in the UK during the Covid-19 outbreak. The Met Police have created a hate crime forum involving Chinese community groups, and community members have (link: https://www.itv.com/news/2020-05-22/east-asian-british-community-calls-for-inquiry-following-three-fold-increase-in-hate-crimes-since-coronavirus-pandemic/ text: called for an inquiry) into recent 'hate crimes'—in response to which Home Secretary Priti Patel has vowed to ensure all "criminals face justice". Even for those generally distrustful of the police, reporting 'hate crimes' might seem like an exceptional case where the police are at least deploying their powers against racists. This piece is intended as something in-between an intervention and a resource on why hate crime legislation does not keep us safe. A genuinely anti-racist response to racist attacks must reject the involvement of the police, which only endangers communities already targeted by police, whilst legitimising the police's role in subordinating Black, Muslim and other racialised and marginalised communities. Building on mutual aid organising under Covid-19, we should instead be developing autonomous practices of community care and safety, and resisting state and police violence everywhere.

*N.B. In this piece, 'hate crimes' against East and Southeast Asians are spoken about as a general phenomenon. This is because it appears that the majority of attacks have been against people who are racialised as 'Chinese', usually light-skinned East and Southeast Asians, due to the origins of the virus in China. However, this categorisation tends to flatten socioeconomic differences, particularly the ways in which many Southeast Asian communities remain marginalised within this grouping, and disproportionately affected by poverty and policing.*

## Situating ‘hate crime’

Like all criminal justice approaches, ‘hate crime’ displaces social problems onto individual ‘criminals’, whose punishment provides the appearance of having addressed the issue. In other words, hate crime law provides us the illusion of safety, while the conditions that give rise to racist abuse remain intact.

Addressing racist attacks means first recognising them as symptoms of deeper issues to be tackled. Clearly it is useful for Western states to find in China a scapegoat for their catastrophic responses to the pandemic—indeed, (link: https://theconversation.com/british-people-blame-chinese-government-more-than-their-own-for-the-spread-of-coronavirus-137642 text: recent polling) suggests British people blame the Chinese government more than they do the British government for the spread of Covid-19 in the UK. But we must also understand the histories and interests that converge in the ‘blame China’ narrative, and which imbue it with power. The virus’ origins in China meant that it would always already be racialised in the West, its genesis and spread seen through the lens of long-standing Orientalist and Sinophobic ideologies that frame Chinese people as dirty, diseased and an 'invasive' threat—tropes often reinforced by a diaspora politics of respectability that distinguishes ‘us’ assimilated Asians from ‘those' 'uncivilised' ones.

> Hate crime law provides us the illusion of safety, while the conditions that give rise to racist abuse remain intact. Addressing racist attacks means first recognising them as symptoms of deeper issues to be tackled.

The current climate also cannot be separated from the US empire’s attempts to contain China’s growing global political and economic influence. Although the ‘blame China’ narrative is primarily being peddled by US politicians and media, it is also being condoned and perpetuated here in the UK. This is something we’d do well to pay attention to and critically strategise about. The unfolding global struggle between the US and China—exacerbated by the current crisis—will likely contribute to a racist climate for those of us racialised as Chinese beyond this moment, while intensifying the underlying crises of global capitalism, hitting hardest those already suffering the most.

All this is obscured by a narrow focus on the policing of ‘hate’ divorced from its proper political context. This focus has only been reinforced by the mainstream media framing of racist attacks as ‘hate crimes’. In line with a broader liberal tendency to individualise structural oppression, racism here tends to be framed as primarily interpersonal, rooted in the irrational prejudice of individual bigots or those particularly impressionable to racist conspiracy theory.

It’s worth noting here that at the same time as engaging Sinophobic tropes, the mainstream media is providing significant coverage of anti-Chinese hate crime, when by comparison there has rarely been such a focus on anti-Black or anti-Muslim hate crime. We cannot simply see this as an extension of benevolent concern to East Asians on the part of moneyed media—it is inseparable from white supremacy’s strategic instrumentalisation of East Asian communities as a way of framing certain racial groups as more deserving of care due to their position as ‘hard-working' and 'law-abiding' model minorities. The flipside of this is the continual denigration of Black and Muslim communities, against whom violence is normalised. Many East Asians granted media platforms to speak out about racism actively participate in this denigration by upholding model minority myths and placing trust in the British state and police. Such appeals to the moral purity of East Asian victims of racist attacks must be understood as an attempt to demonstrate our proximity to whiteness, and in turn, our entitlement to safety and protection by the state—legitimising violence against those who cannot or will not meet such standards.

> This media coverage of ‘hate crime’ also renders ‘coronavirus racism’ synonymous with interpersonal racism towards East and Southeast Asian people, obscuring the reality of structural pandemic racism, which Black communities are bearing the brunt of.

This media coverage of ‘hate crime’ also renders ‘coronavirus racism’ synonymous with interpersonal racism towards East and Southeast Asian people, obscuring the reality of structural pandemic racism, which Black communities are bearing the brunt of. (link: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/07/black-people-four-times-more-likely-to-die-from-covid-19-ons-finds text: ONS statistics) are showing that Black people are four times more likely to die from Covid-19 than white people, with Bangladeshi and Pakistani people almost twice as likely. The British government is still failing to provide adequate PPE to all key workers, failing to provide welfare support for key workers and renters, keeping people locked up in prisons and detention centres, and maintaining a hostile environment for migrants, on top of restrictive visa conditions. These are just some of the murderous policies of inaction that are (link: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/20/coronavirus-racial-inequality-uk-housing-employment-health-bame-covid-19 text: exacerbating existing inequalities) and disproportionately killing black and brown people—willingly sacrificed just so that Britain can continue ‘business as usual’.

Within East and Southeast Asian communities, migrant workers are being hit the hardest, with the Filipinx community suffering the (link: https://metro.co.uk/2020/05/17/filipino-frontline-workers-suffer-highest-coronavirus-death-rate-uk-healthcare-system-12716971/ text: highest death rate) amongst healthcare workers. We have also heard from Vietnamese undocumented workers with coronavirus symptoms who are not accessing healthcare for fear of being charged fees they cannot afford or being reported to the Home Office. This state racism is not accidental or exceptional, but is part and parcel of Britain’s long imperialist tradition of securing its own interests through the exploitation of racialised and colonised people. Such structural racism is obscured when ‘hate crimes’ become exemplary of racism. By reframing racism as interpersonal and criminalising racist individuals, hate crime law allows the state to write its own racism out the picture.

## The violence of policing The involvement of police in addressing ‘hate crime’ creates a situation where many people routinely targeted by the police are apparently supposed to rely on them when they suffer racist attacks. For instance, migrant workers in Chinatowns and Vietnamese nail bars who experience racist abuse are supposed to seek help from the same police that conduct violent immigration raids in their workplaces. For undocumented people who are criminalised simply for living and working in this country, reporting hate crimes means risking arrest, even detention or deportation. The reality is that hate crime legislation was never meant to protect them. It is a way for the police to appear that it is on our communities’ side in an attempt to gain legitimacy. It functions to divide communities along lines of race and class by appearing to offer protection to those minority citizens (e.g. middle-class East Asians) who are generally shielded from the impacts of police violence, whilst justifying the expansion of policing and surveillance powers which primarily target poor, Black, Muslim and undocumented communities. > [Hate crime law] is a way for the police to appear that it is on our communities’ side in an attempt to gain legitimacy [...] whilst justifying the expansion of policing and surveillance powers which primarily target poor, Black, Muslim and undocumented communities. This is part of a broader pattern of state co-option of anti-oppression struggles to pit communities against each other. As Lynn Ly argued on a recent (link: https://www.facebook.com/HCCIHamilton/videos/260945371693353/ text: webinar), the same anti-hate crime rhetoric that frames the state as the protector of marginalised people is often mobilised to justify the expansion of security regimes at home and abroad. Speaking from a North American context, Ly gave the example of how LGBT mobilisation against ‘hate crime’ coincided with significant increases in military spending, with ‘LGBT rights’ weaponised as a justification for increased surveillance and military intervention in the War on Terror. Police powers have already been expanded under Covid-19—we’ve seen countless footage of police out in packs, failing to adhere to physical distancing guidelines and harassing disproportionately working class and Black people just for being outside. Meanwhile the (link: https://twitter.com/rebellious_scot/status/1258865922229637121?s=20 text: British media) celebrated the 'war-time spirit' of white Britons gathering for VE Day street parties. We don’t need more police on the streets endangering marginalised people in the name of ‘our’ ‘safety’. It’s also important to consider the effects of racism in the policing of perpetrators. In the context of anti-Black racist ideologies that frame Black men in particular as prone to violence and criminality, we can expect racialised assessments of risk to inform how and whether hate crime cases are pursued—both by the police and by members of affected communities. Indeed, daikon* have heard from contacts that a video of a Black man calling for Black people to attack Chinese people (in the wake of news about racism towards African migrants in Guangzhou) has been circulated on the Met Police hate crime forum, to which some Chinese ‘community leaders’ have responded with demands for punishment and calls for massive escalation—to report it to the Chinese embassy to warn Chinese people globally of the threat. This example betrays not only anti-Black panic, but a commitment only to a narrow, self-protective ‘anti-racism’ that fails to appreciate, if not actively endorses, the role of the police in brutalising Black people and communities. Any community response to racist attacks must keep everyone safe. Channelling energy into punishment of individual perpetrators delivers just that—punishment, not safety—whilst failing to address the root causes of Sinophobia and their manifestations in different communities, and ignoring the structural racism of the police. We need to recognise the police as an institution that upholds white supremacy, and refuse collaboration and complicity with the police and whiteness. > We need to recognise the police as an institution that upholds white supremacy, and refuse collaboration and complicity with the police and whiteness. Relying on the state for protection divides communities in other ways too. As Jon Burnett has (link: https://sci-hub.tw/10.1177/0306396813475981 text: argued), when hate becomes criminalised, it is the state that gets to set the agenda and priorities for fighting ‘hate’ according to its interests. This forces different communities into competition with each other for state recognition and limited funding for their causes, managed through ‘community leaders’ (often simple nationalists) who are not accountable to or necessarily representative of the diverse communities they claim to represent. This discourages criticism of the police and state agencies, whilst encouraging competition and enmity between communities. In this moment, it is important to recognise that it is not just East and Southeast Asian people experiencing Covid-related ‘hate crimes’—a Black transport worker Belly Mujinga recently died of Covid-19 after a man spat on her claiming to have coronavirus; the Monitoring Group have (link: http://www.irr.org.uk/news/race-hate-crimes-collateral-damage-of-covid-19/ text: reported) increasingly violent language used towards Black people; and an empowered far-right are circulating antisemitic conspiracy theories and spreading fake news that Muslims are violating social distancing guidelines. We need to be paying attention to the various ways that existing racisms are emboldened and used to scapegoat marginalised people in times of crisis, and build on-the-ground coalitions beyond and against the state—whose policies and media narratives are always the cause of flare-ups in racist attacks, and who enforce a system that places racialised communities at closer proximity to violence and death.

## Alternatives to calling the police Hate crime statistics suggest that reported hate crimes against East and Southeast Asians have tripled during the coronavirus outbreak. The risk and fear are real. It's crucial that we build on and develop practices of community care and safety that are independent of the police. Please consider the following suggestions an invitation to think together about how we can keep our communities safe. **Bystander intervention** One useful practice in terms of prevention and de-escalation is bystander intervention. Bystander intervention broadly involves recognising a (potentially) harmful situation and choosing to intervene to prevent (further) harm. It recognises that perpetrators of ‘hate crimes’ are empowered by particular media-fuelled climates of racist hostility because they feel their behaviour is legitimised and, often correctly, believe that no-one will intervene. It can also encourage other bystanders who might otherwise be afraid or unsure of how to intervene to get involved, thereby creating collective resistance that pushes back against a climate of complicity. Further, often part of the harm of racist abuse is feeling isolated and doubly degraded by being ignored. Being an active bystander communicates to the victim that you recognise and reject the harm being done. Bystander intervention can take a range of forms. Importantly, it need not involve directly confronting the perpetrator, which often risks escalating the situation. Below is a useful general guide: “Don’t be a Bystander: 6 Tips for Responding to Racist Attacks”, an abolitionist approach to bystander intervention by BCRW and Project Nia. (embed: https://vimeo.com/199947156)

Under social distancing, some of the recommended courses of action will not be possible, but the principles are the same. Active bystanders can still focus on the person targeted from a suitable distance—wave to them to see if they need support, pretend you know each other, get others’ attention, document the incident with their consent, and check in after the incident. There are some useful graphics (link: https://www.instagram.com/p/B_xHoK_AE8z/ text: here) from Cradle Community about bystander intervention during social distancing. Chinese for Affirmative Action have also produced (link: https://caasf.org/2020/05/what-to-do-when-you-see-or-experience-covid-19-hate/ text: useful resources) for what to do when experiencing or witnessing racist abuse. **Autonomous care and support networks** Bystander intervention can be useful to prevent harm in the moment, but we also need ongoing forms of care and support. These of course already exist in our personal relationships and communities, and sometimes the most helpful thing to do if you experience racist abuse is to reach out to friends and people you trust to talk about what happened. However, there are those for whom existing networks cannot meet their needs—they may face gaslighting or incomprehension. There is a need to develop community initiatives amongst people who can better understand and support each other that are accessible independently of reporting to the police. There have been some community initiatives in this vein, for example, the discussion session after Youngsook Choi’s interactive performance piece ‘(link: https://youngsookchoi.com/unapologetic-coughing text: Unapologetic Coughing)’, which brought together primarily East and Southeast Asian diaspora folks to discuss practical and healing actions in the face of 'epidemic racism'. Kanlungan Filipino Consortium are also offering (link: https://www.facebook.com/kanlunganuk/posts/3029691207095968 text: free consultations) for mental health issues related to Covid-19. There are also excellent general resources being developed by grassroots groups. Sisters Uncut have produced a useful resource on ‘(link: http://www.sistersuncut.org/2020/05/13/caring-for-each-other-during-covid/ text: Caring for Each Other During Covid)’, which outlines some strategies for responding to harm whether you are experiencing harm or supporting someone else who has been harmed. **Community archiving** We are currently facing a government rewriting their own complicity in mass death out of history. It is crucial to recognise and remember what is actually happening at this time (and always). In terms of racism towards East and Southeast Asian communities under Covid-19, we need to think about developing methods of archiving stories and incidents that do not rely on or involve reporting to police. (link: http://attitudes.site text: Here) is one volunteer-run initiative that archives data and stories on discrimination against East Asians and Southeast Asians. It allows individuals to report their own experiences and submit social media posts, news articles, etc. We are hoping to run some workshops on police violence and alternatives to calling the police in the near future. Watch this space!

## The violence of policing The involvement of police in addressing ‘hate crime’ creates a situation where many people routinely targeted by the police are apparently supposed to rely on them when they suffer racist attacks. For instance, migrant workers in Chinatowns and Vietnamese nail bars who experience racist abuse are supposed to seek help from the same police that conduct violent immigration raids in their workplaces. For undocumented people who are criminalised simply for living and working in this country, reporting hate crimes means risking arrest, even detention or deportation. The reality is that hate crime legislation was never meant to protect them. It is a way for the police to appear that it is on our communities’ side in an attempt to gain legitimacy. It functions to divide communities along lines of race and class by appearing to offer protection to those minority citizens (e.g. middle-class East Asians) who are generally shielded from the impacts of police violence, whilst justifying the expansion of policing and surveillance powers which primarily target poor, Black, Muslim and undocumented communities. > [Hate crime law] is a way for the police to appear that it is on our communities’ side in an attempt to gain legitimacy [...] whilst justifying the expansion of policing and surveillance powers which primarily target poor, Black, Muslim and undocumented communities. This is part of a broader pattern of state co-option of anti-oppression struggles to pit communities against each other. As Lynn Ly argued on a recent (link: https://www.facebook.com/HCCIHamilton/videos/260945371693353/ text: webinar), the same anti-hate crime rhetoric that frames the state as the protector of marginalised people is often mobilised to justify the expansion of security regimes at home and abroad. Speaking from a North American context, Ly gave the example of how LGBT mobilisation against ‘hate crime’ coincided with significant increases in military spending, with ‘LGBT rights’ weaponised as a justification for increased surveillance and military intervention in the War on Terror. Police powers have already been expanded under Covid-19—we’ve seen countless footage of police out in packs, failing to adhere to physical distancing guidelines and harassing disproportionately working class and Black people just for being outside. Meanwhile the (link: https://twitter.com/rebellious_scot/status/1258865922229637121?s=20 text: British media) celebrated the 'war-time spirit' of white Britons gathering for VE Day street parties. We don’t need more police on the streets endangering marginalised people in the name of ‘our’ ‘safety’. It’s also important to consider the effects of racism in the policing of perpetrators. In the context of anti-Black racist ideologies that frame Black men in particular as prone to violence and criminality, we can expect racialised assessments of risk to inform how and whether hate crime cases are pursued—both by the police and by members of affected communities. Indeed, daikon* have heard from contacts that a video of a Black man calling for Black people to attack Chinese people (in the wake of news about racism towards African migrants in Guangzhou) has been circulated on the Met Police hate crime forum, to which some Chinese ‘community leaders’ have responded with demands for punishment and calls for massive escalation—to report it to the Chinese embassy to warn Chinese people globally of the threat. This example betrays not only anti-Black panic, but a commitment only to a narrow, self-protective ‘anti-racism’ that fails to appreciate, if not actively endorses, the role of the police in brutalising Black people and communities. Any community response to racist attacks must keep everyone safe. Channelling energy into punishment of individual perpetrators delivers just that—punishment, not safety—whilst failing to address the root causes of Sinophobia and their manifestations in different communities, and ignoring the structural racism of the police. We need to recognise the police as an institution that upholds white supremacy, and refuse collaboration and complicity with the police and whiteness. > We need to recognise the police as an institution that upholds white supremacy, and refuse collaboration and complicity with the police and whiteness. Relying on the state for protection divides communities in other ways too. As Jon Burnett has (link: https://sci-hub.tw/10.1177/0306396813475981 text: argued), when hate becomes criminalised, it is the state that gets to set the agenda and priorities for fighting ‘hate’ according to its interests. This forces different communities into competition with each other for state recognition and limited funding for their causes, managed through ‘community leaders’ (often simple nationalists) who are not accountable to or necessarily representative of the diverse communities they claim to represent. This discourages criticism of the police and state agencies, whilst encouraging competition and enmity between communities. In this moment, it is important to recognise that it is not just East and Southeast Asian people experiencing Covid-related ‘hate crimes’—a Black transport worker Belly Mujinga recently died of Covid-19 after a man spat on her claiming to have coronavirus; the Monitoring Group have (link: http://www.irr.org.uk/news/race-hate-crimes-collateral-damage-of-covid-19/ text: reported) increasingly violent language used towards Black people; and an empowered far-right are circulating antisemitic conspiracy theories and spreading fake news that Muslims are violating social distancing guidelines. We need to be paying attention to the various ways that existing racisms are emboldened and used to scapegoat marginalised people in times of crisis, and build on-the-ground coalitions beyond and against the state—whose policies and media narratives are always the cause of flare-ups in racist attacks, and who enforce a system that places racialised communities at closer proximity to violence and death.

## Alternatives to calling the police Hate crime statistics suggest that reported hate crimes against East and Southeast Asians have tripled during the coronavirus outbreak. The risk and fear are real. It's crucial that we build on and develop practices of community care and safety that are independent of the police. Please consider the following suggestions an invitation to think together about how we can keep our communities safe. **Bystander intervention** One useful practice in terms of prevention and de-escalation is bystander intervention. Bystander intervention broadly involves recognising a (potentially) harmful situation and choosing to intervene to prevent (further) harm. It recognises that perpetrators of ‘hate crimes’ are empowered by particular media-fuelled climates of racist hostility because they feel their behaviour is legitimised and, often correctly, believe that no-one will intervene. It can also encourage other bystanders who might otherwise be afraid or unsure of how to intervene to get involved, thereby creating collective resistance that pushes back against a climate of complicity. Further, often part of the harm of racist abuse is feeling isolated and doubly degraded by being ignored. Being an active bystander communicates to the victim that you recognise and reject the harm being done. Bystander intervention can take a range of forms. Importantly, it need not involve directly confronting the perpetrator, which often risks escalating the situation. Below is a useful general guide: “Don’t be a Bystander: 6 Tips for Responding to Racist Attacks”, an abolitionist approach to bystander intervention by BCRW and Project Nia. (embed: https://vimeo.com/199947156)

Under social distancing, some of the recommended courses of action will not be possible, but the principles are the same. Active bystanders can still focus on the person targeted from a suitable distance—wave to them to see if they need support, pretend you know each other, get others’ attention, document the incident with their consent, and check in after the incident. There are some useful graphics (link: https://www.instagram.com/p/B_xHoK_AE8z/ text: here) from Cradle Community about bystander intervention during social distancing. Chinese for Affirmative Action have also produced (link: https://caasf.org/2020/05/what-to-do-when-you-see-or-experience-covid-19-hate/ text: useful resources) for what to do when experiencing or witnessing racist abuse. **Autonomous care and support networks** Bystander intervention can be useful to prevent harm in the moment, but we also need ongoing forms of care and support. These of course already exist in our personal relationships and communities, and sometimes the most helpful thing to do if you experience racist abuse is to reach out to friends and people you trust to talk about what happened. However, there are those for whom existing networks cannot meet their needs—they may face gaslighting or incomprehension. There is a need to develop community initiatives amongst people who can better understand and support each other that are accessible independently of reporting to the police. There have been some community initiatives in this vein, for example, the discussion session after Youngsook Choi’s interactive performance piece ‘(link: https://youngsookchoi.com/unapologetic-coughing text: Unapologetic Coughing)’, which brought together primarily East and Southeast Asian diaspora folks to discuss practical and healing actions in the face of 'epidemic racism'. Kanlungan Filipino Consortium are also offering (link: https://www.facebook.com/kanlunganuk/posts/3029691207095968 text: free consultations) for mental health issues related to Covid-19. There are also excellent general resources being developed by grassroots groups. Sisters Uncut have produced a useful resource on ‘(link: http://www.sistersuncut.org/2020/05/13/caring-for-each-other-during-covid/ text: Caring for Each Other During Covid)’, which outlines some strategies for responding to harm whether you are experiencing harm or supporting someone else who has been harmed. **Community archiving** We are currently facing a government rewriting their own complicity in mass death out of history. It is crucial to recognise and remember what is actually happening at this time (and always). In terms of racism towards East and Southeast Asian communities under Covid-19, we need to think about developing methods of archiving stories and incidents that do not rely on or involve reporting to police. (link: http://attitudes.site text: Here) is one volunteer-run initiative that archives data and stories on discrimination against East Asians and Southeast Asians. It allows individuals to report their own experiences and submit social media posts, news articles, etc. We are hoping to run some workshops on police violence and alternatives to calling the police in the near future. Watch this space!